The increase in retractions, or withdrawals, of scientific articles is a growing reality in Swiss research, with 304 cases identified since the 1990s, the majority of which date back to recent years. Experts believe this rise reflects increased rigor rather than lack of reliability. However, some cases are concerning.

The number of retractions of scientific papers worldwide has been following an exponential curve since the early 2000s, according to the Retraction Watch database, which tracks these articles. In 2023, nearly 10,000 publications were retracted, corrected, or raised concerns about their scientific quality, setting an all-time record.

The retraction of a scientific paper is never trivial. In the scientific process, the publication of an article is considered a culmination, and the research that relies on it before being questioned may not necessarily be corrected. An article on stem cells published in the prestigious journal Nature in 2002 and retracted only this year has been cited nearly 4,500 times in the meantime.

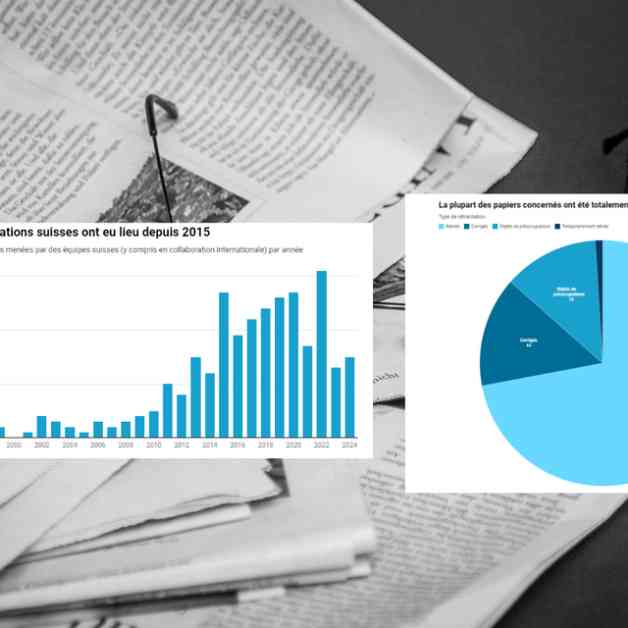

Swiss research is not immune to this phenomenon, according to an analysis by the RTS of the Retraction Watch database. The number of retractions of research conducted by Swiss teams – including international collaborations – follows a similar trend to the global average, with a total of 304 retractions since 1991. More than three-quarters of retractions have taken place in the last decade, with 2022 being the most significant year, with 32 affected studies.

There are several “types” of retractions. Firstly, there are articles that are simply withdrawn, accounting for nearly three-quarters of Swiss cases. This is followed by articles that have been corrected after publication. Some raise concerns about their scientific quality. These two types of retractions each represent just over 10% of cases. Finally, three papers have been “reinstated” after being temporarily withdrawn for issues such as notice.

Many articles on health make up a significant portion of retractions, with nearly half of the corpus involving health or medical-related research. This is not surprising to Guillaume Levrier, a researcher specializing in biotechnologies and a member of the NanoBubbles network, which tracks scientific errors and frauds.

The palm for the highest number of Swiss retractions goes to a researcher at the University of Lugano, with six papers retracted, seven corrected, and one raising concerns. Most cases involve plagiarism issues. The pressure to publish, prevalent in the scientific world, can drive researchers to commit fraud.

While not all errors are intentional, the majority of researchers are honest in their work. However, fraudulent researchers, although few in number, tend to be prolific. The reasons for Swiss retractions range from simple errors to ethical problems, including data errors, image issues, analysis errors, questions about the researchers’ work, plagiarism, and falsification.

The increase in Swiss retractions may not necessarily harm the credibility of Swiss research, as it could indicate a strengthening of scientific rigor. Strengthening verification protocols before publication could eliminate errors, but it may be more beneficial to focus on international cooperation and initiatives to broaden evaluation criteria beyond quantitative indicators.