The Xiao River, a lifeline for the people of southern China, has witnessed its fair share of tragedy and horror. Flowing from the mountains into a plain dotted with paddies and villages, this once serene river became a conduit for a gruesome chapter in history. In August 1967, over nine thousand individuals met their untimely demise in the region of Hunan province through brutal acts of violence. Dao county, where the Xiao River cuts through on its journey northward, bore the brunt of this atrocity, with half of its 400,000 residents falling victim to the bloodshed.

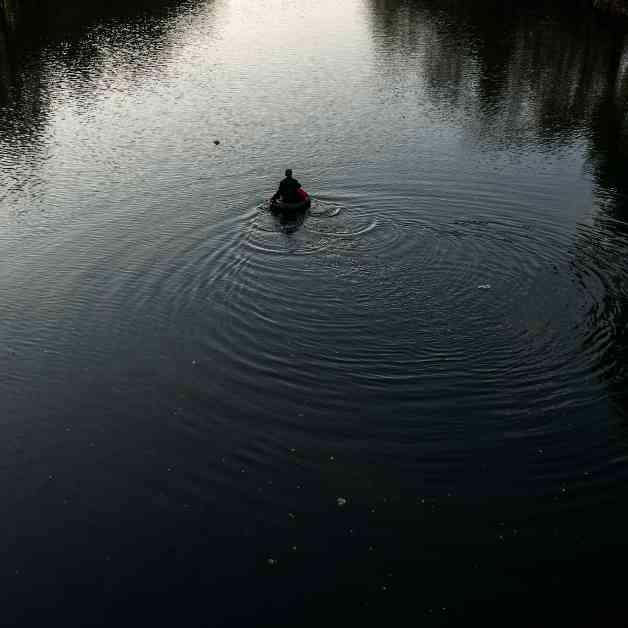

The victims of this massacre were subjected to unimaginable horrors – from being bludgeoned to death with agricultural tools to being tossed into the river like mere objects. Some were even tied together with wire, forming macabre chains of death that floated downstream. The once pristine river became a macabre sight, with observers on the shore counting a hundred corpses passing by every hour. Children, desensitized by the carnage, ran along the banks competing to spot the most bodies. The gruesome scene finally came to a halt at the Shuangpai dam, where the bodies clogged the hydropower generators, halting the flow of electricity and contaminating the waterways.

For decades, this dark chapter in China’s history remained shrouded in secrecy and denial. The massacre was often dismissed as a consequence of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, with Dao county being portrayed as a remote and backward region where such atrocities were bound to occur. The presence of the Yao minority in the area was used as a scapegoat, perpetuating racist stereotypes about their supposed uncivilized nature. However, these explanations fail to capture the true essence of what occurred in Dao county.

Contrary to popular belief, Dao county is a cradle of Chinese civilization, boasting a rich cultural heritage that extends back centuries. The perpetrators of the massacre were not frenzied peasants but rather members of the Han Chinese majority, who targeted their own people in a systematic campaign of violence. The victims were deemed subhuman by the Communist Party cadres who orchestrated the killings, branding them as enemies of the state and justifying their slaughter as a necessary purge of society.

The truth about the massacre in Dao county would have remained buried if not for the relentless efforts of one individual – Tan Hecheng. A dedicated editor and researcher, Tan unearthed the harrowing details of the event in the 1980s and has since devoted his life to shedding light on this dark chapter of history. His work, culminating in the publication of his findings in 2011 and subsequent updates in 2016, has brought the story of Dao county to the forefront, challenging the prevailing narratives of denial and amnesia.

Tan’s quest for truth has not been without its challenges. Despite facing opposition from both local residents and government authorities, he continues to pursue his research with unwavering determination. His work has sparked controversy and debate, forcing many to confront the uncomfortable truths of their past and present. Through his tireless efforts, Tan has become a symbol of resistance and resilience, a voice for the voiceless victims of Dao county’s massacre.

Accompanied by photographer and artist Sim Chi Yin, Tan delves deeper into the heart of Dao county, seeking out the stories and memories that linger in its landscape. Together, they traverse the lush mountains and rugged terrain, immersing themselves in the echoes of the past that reverberate through the land. Through their journey, they capture the traces of history that lie hidden beneath the surface, illuminating the enduring legacy of the massacre and its impact on the present.

In November 2016, Sim Chi Yin’s photographs captured the haunting beauty of Dao county’s landscapes, juxtaposed against the dark shadows of its history. From serene hillsides to somber riverbanks, each image tells a story of loss and resilience, of memory and forgetting. These visual narratives, featured in Tan’s book “Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future,” serve as a poignant reminder of the power of remembrance and the importance of confronting the past.

As Tan Hecheng and Sim Chi Yin continue their exploration of Dao county, they unravel the layers of history that have been buried and forgotten. Their work serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of the massacre, a reminder of the human capacity for both cruelty and compassion. Through their efforts, they strive to honor the memory of the victims and ensure that the truth of what transpired in Dao county will never be erased from the annals of history.

Uncovering the Truth

The massacre in Dao county stands as a stark reminder of the darker side of human nature, where ideology and power converge to justify unspeakable acts of violence. The perpetrators of this atrocity, driven by a fervent belief in their cause, unleashed a wave of terror that reverberated throughout the region. Tan Hecheng’s relentless pursuit of the truth has brought to light the untold stories of those who perished, giving voice to the voiceless and challenging the prevailing narratives of denial and distortion.

A Legacy of Resilience

Despite the horrors of the past, the people of Dao county have shown remarkable resilience in the face of adversity. Through their enduring spirit and unwavering commitment to truth and justice, they have refused to let the memory of the massacre fade into obscurity. Tan Hecheng and Sim Chi Yin’s work serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of those who perished, a reminder of the human capacity for both cruelty and compassion.

Remembering the Past, Shaping the Future

As we confront the painful truths of history, we are confronted with the dual nature of memory – both a burden and a blessing. The stories of Dao county’s massacre serve as a cautionary tale, a reminder of the dangers of unchecked power and the importance of preserving the memory of those who have suffered. Through the work of individuals like Tan Hecheng and Sim Chi Yin, we are reminded of the power of remembrance and the imperative of bearing witness to the past.